Mirages and Fallen Angels: warnings from the McCarthy era echo down the years

The stories of how a book was written, a film made, and of an advert in a paperback, all from over 50 years ago, are still important today, says Adam Jezard

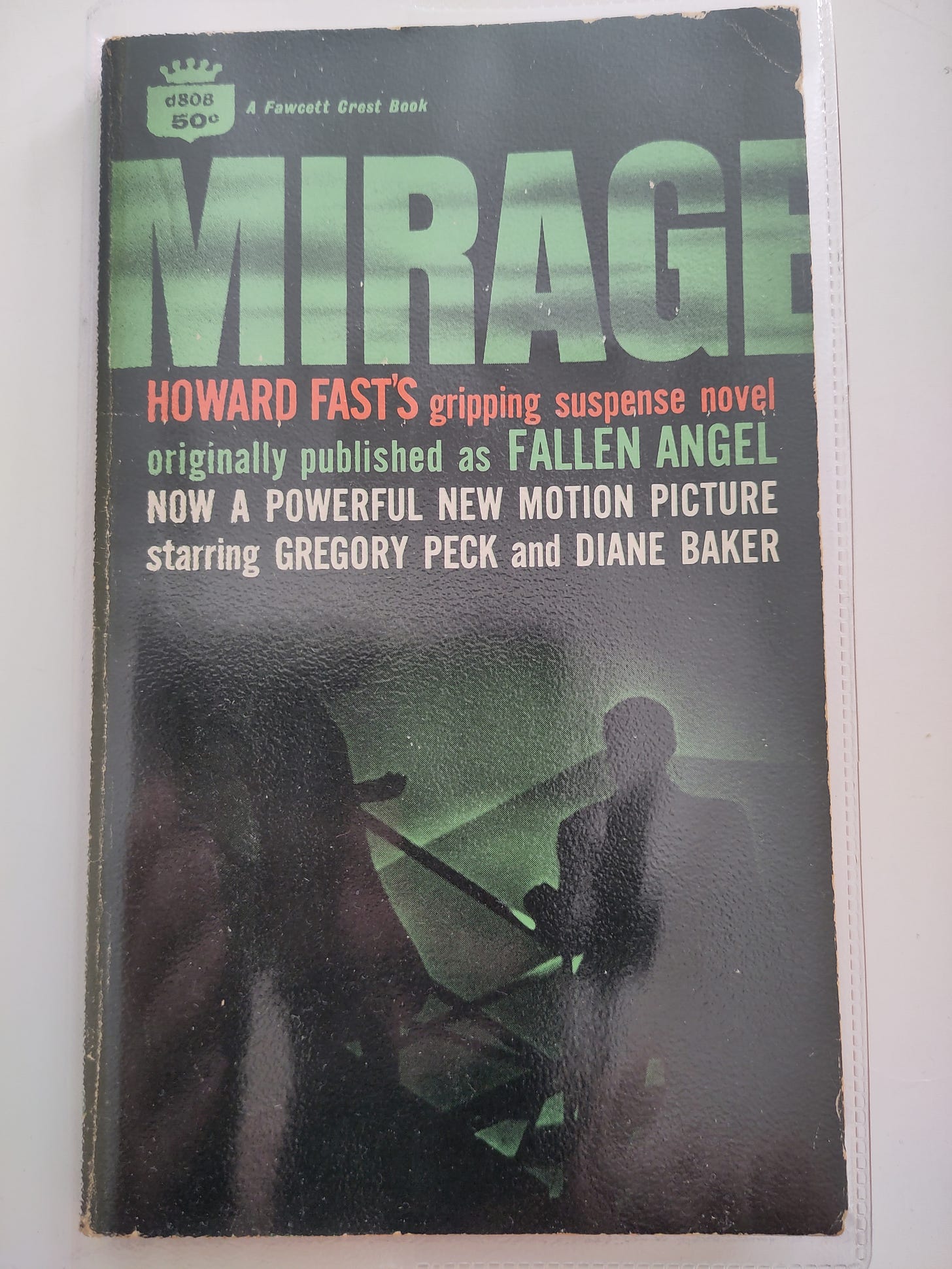

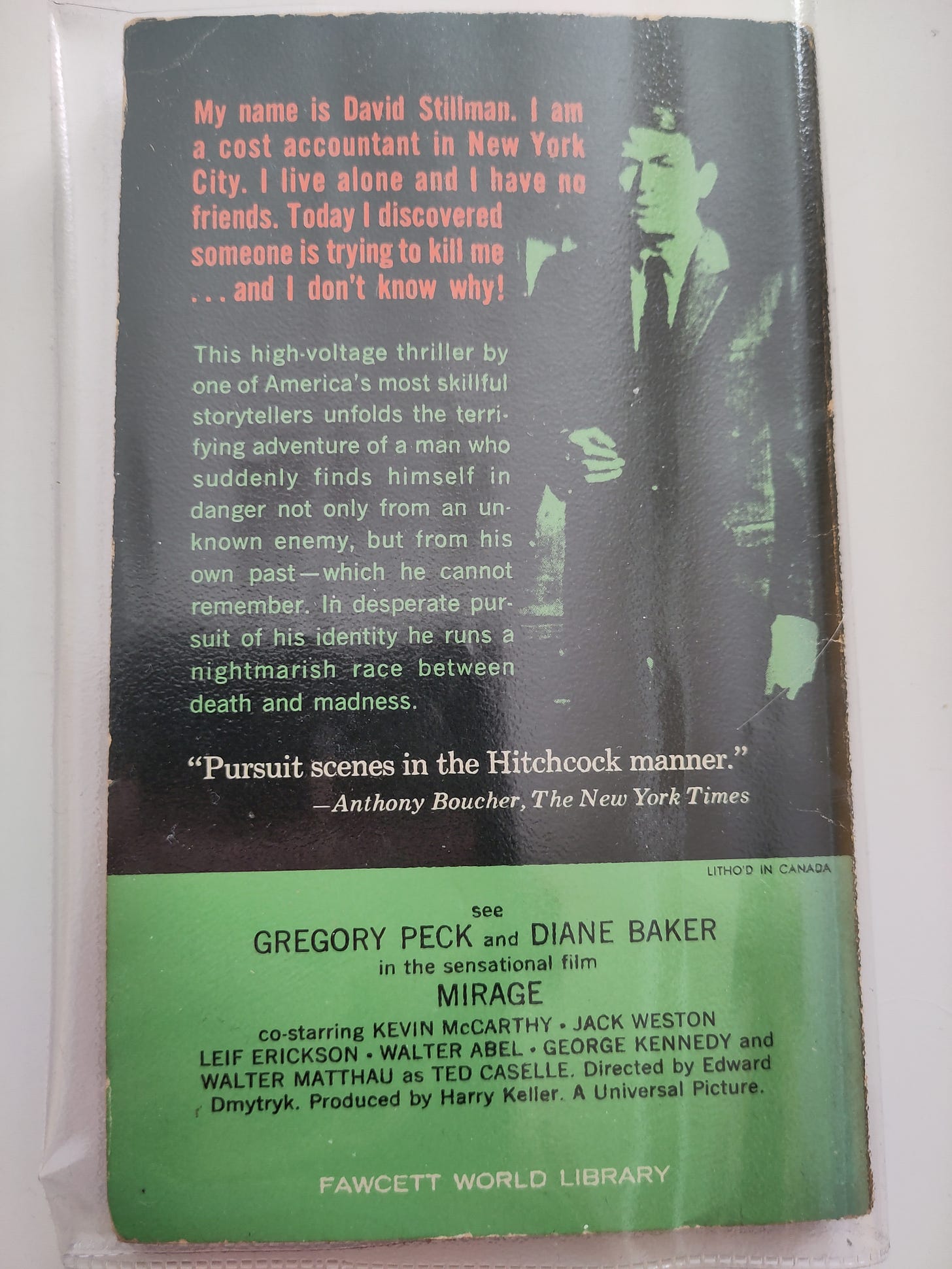

Every book I own tells a story and it's not just the one between the covers. This is the movie tie-in edition of Howard Fast's Fallen Angel, aka Mirage, the film of which is often described as one of the best Hitchcock films he never directed. It is a thrilling movie, with a music score by Quincy Jones, a cast featuring Gregory Peck, George Kennedy and Diane Baker, with a great turn by Walter Matthau as a down-at-heel PI, and with a thrilling script by Peter (Charade, Arabesque, Taking of Pelham 1,2,3) Stone.

But behind the book and the film there is a tale of the rise of fascism in America, of "cancelling" opposing voices in the most punitive way, of betrayal, and of demagogues, fictional and real, misusing technology and politics to achieve their own despicable ends that holds important messages for us today.

Early on in Mirage Two men enter an elevator and a feminised electronic voice asks them which floors they want. One comments he misses the old guys who used to run the elevators, the other that perhaps one day the robots will keep humans as pets.

The talk is strikingly modern and could be from a comedy of the era, but Mirage is a paranoid thriller deeply rooted in the nuclear fears of the Cold War era while Fallen Angel is from an even more paranoid period just a few years previously, when Senator Joseph McCarthy dominated US politics with a witch-hunt aimed at rooting out communism from American life, and particularly from American media: cinema, radio, publishing and television.

The writer of Fallen Angel was best-seller Howard Fast, who originally published it under a pseudonym as he had been imprisoned and black-listed after refusing to “name names” before Senator McCarthy’s House American Un-activities Commission. Fast had been asked to betray people who'd have received the same fate that he’d suffered. Their “crime” had been to contribute to a fund for orphans of US veterans killed fighting the fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

Prison led Fast to write his best-known work, Spartacus, on which the famed film scripted by fellow blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo is based. However, his earlier stories, both that of his own life in the McCarthy era and that of Fallen Angel, which features a villainous demagogic Trump-like industrialist, tell us something about the fear of the human species at times of great social upheaval and technical change; they show how our concerns can be manipulated by so-called populists seeking self-aggrandisement so they can capture, or at least try to seize, whole nation states for their own malign, and usually kleptomaniac, purposes. The villain of the piece has been using the front of a charity working for world peace to get scientists to develop a nuclear weapon that can wipe out populations without the risk of radiation, making them more commercial.

The cultish religious overtones of the book’s title “fallen angel” refers to both the apparently saintly man who fronts the supposed charity and the industrialist who secretly pays the other to front a charitable organisation so convincing peace-loving scientists to work to make weapons without realising it. Their fall in grace is both in one sense metaphorical, as they lose their god-like image in the eyes of the hero of the story, one of their followers, and literal as they get their comeuppances: one even falls from a great height. As for the film’s name “mirage”, this alludes to the temporary amnesia of the hero as well as the mythical aura the narrative’s demagogues weave around themselves. Strong images in relation to today’s rising tide of authoritarianism.

Fast said of the book: "It was a sort of anti-fascist mystery, a form I had never attempted before." One important aspect of the film's production is worthy of note: the director was cult film-maker Edward Dmytryk, who was also one of the Hollywood 10 who served time in prison for refusing to testify before the notorious McCarthy HUAC hearings - the last time before Trump fascism gripped the US. Dmytryk eventually named names to save his career and, despite directing the film of Fast's book, the two reportedly never reconciled over the director's behaviour.

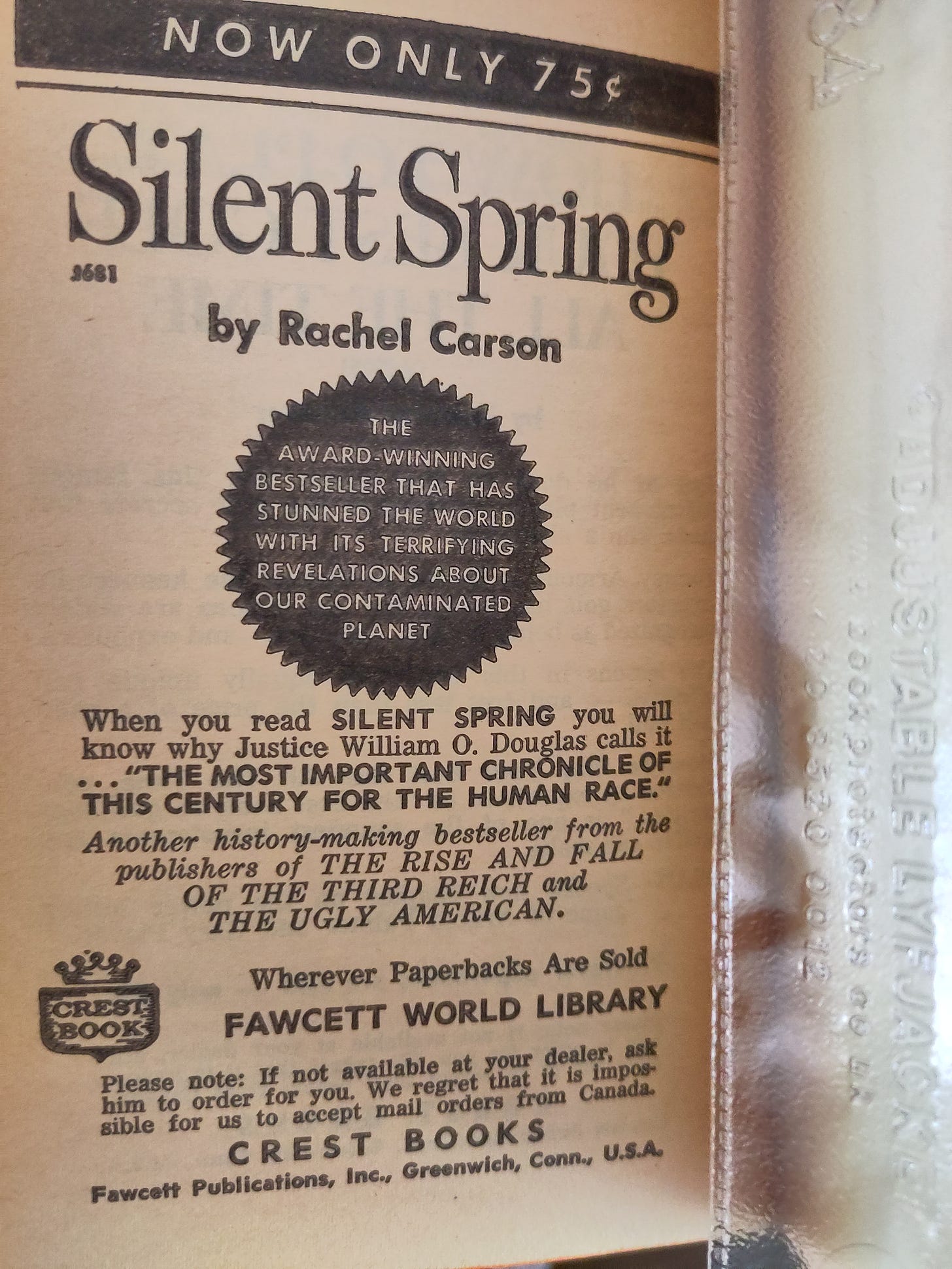

And there's an interesting footnote about the physical copy of the book itself, the last page is an advert for Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, the first warning about the harm man's commercialism was having on wildlife and the planet by exposing the damage caused by the insecticide DDT.

The book and the film are warnings from a past era when America was in the grip of a "strong man" driven by an insane ideological vision. Today other "strong men" are using far-right messaging and tactics that have long crossed the line between freedom of speech and fascism, by banning books, by "cancelling" opponents, by violating the human rights of women and minorities, by casting any opposition as "left-wing" or "woke". With the stripping of protections for the environment, by trashing the necessary net-zero policies, by casting legitimate protest against such moves as criminal, the far- and extreme right that are gripping the west are also ignoring Carson's warning of the damages man is doing to the environment in the name of wealth.

Never has the story of the writing of a book, or of the film made from it, or of an innocent-looking advert in the back of a paperback, been more relevant. The warnings of all three are startlingly prescient to 2025 - and beyond - if we continue to ignore them.